Golden Rule Poetry Anthology

Overview:

We are all alike; we are all different. Students will explore their similarities and differences through poetry. In this poetry study, they will be immersed in reading and writing poems.They will learn about and utilize a variety of poetic tools to create original poems. Their culminating project is a collection of published and original poems which reflect their own individuality.

The full study will take 4 to 5 weeks.

Enduring Understandings/ Essential Questions

- We are all alike; we are all different.

- The diversity of the citizens of the world is essential to the welfare of the world and its inhabitants.

- Our individuality can be reflected in a variety of ways including but not limited to: our words, our interests and our actions.

- What are ways that people of the world are the same? What are some ways they may be different?

- How does world diversity create a better world?

- How do you show your individuality?

- Grade

- 9-12

- Theme

- Four Freedoms

- Length

- The activities may take 4 to 5 weeks.

- Discipline

- Social Studies; Language Arts: Reading; Language Arts: Writitng

- Vocabulary

- Individuality; Diversity; Anthology

Objectives:

- Students will recognize the unique qualities and characteristics that contribute to their own individuality.

- Students will read and analyze poems by a wide variety of poets, modern and classical.

- Students will write a variety of poems, using different styles and formats.

- Students will create a collection of published and original poems that reflect their individuality.

- Students will write a reflective essay which analyzes their collection and how this collection reflects their individuality.

- Students will create a one of a kind portrait of themselves for the cover of their poetry collection.

Background:

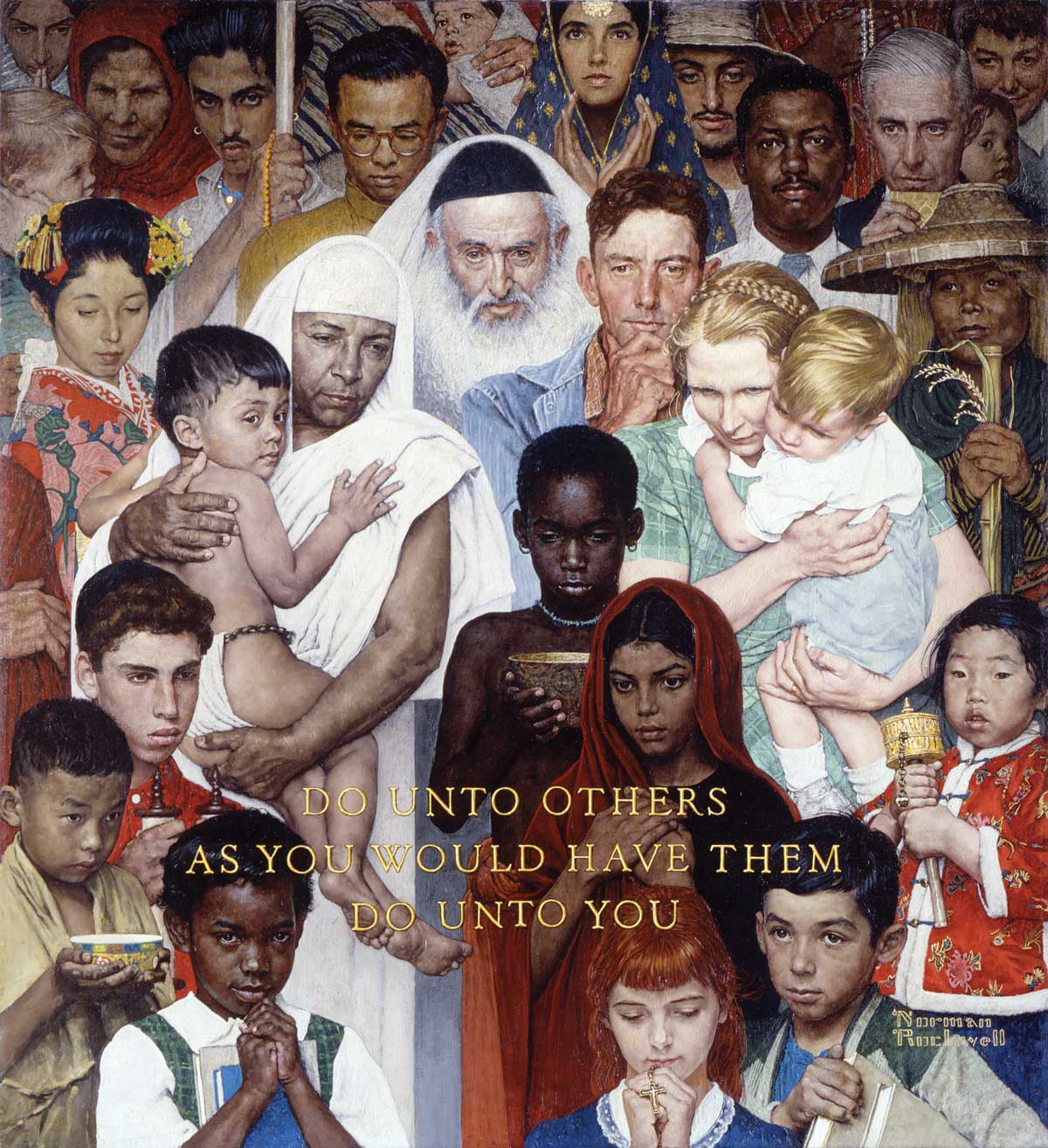

Norman Rockwell is a storyteller. He painted pictures that were seen on the cover of a magazine called The Saturday Evening Post for 47 years. His paintings, also referred to as illustrations, reflected life in America. They also served to draw attention to ideas that Rockwell felt were important, and that he wanted people to think about.

In preparing to paint this 1961 Saturday Evening Post cover, Rockwell noted that many countries, cultures, and religions incorporate some version of The Golden Rule into their belief system. “Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You” was a simple but universal phrase that reflected the artist’s personal philosophy. A gathering of people from different cultures, religions, and ethnicities, this image was a precursor of the socially conscious subjects that he would illustrate in the 1960s and 1970s.

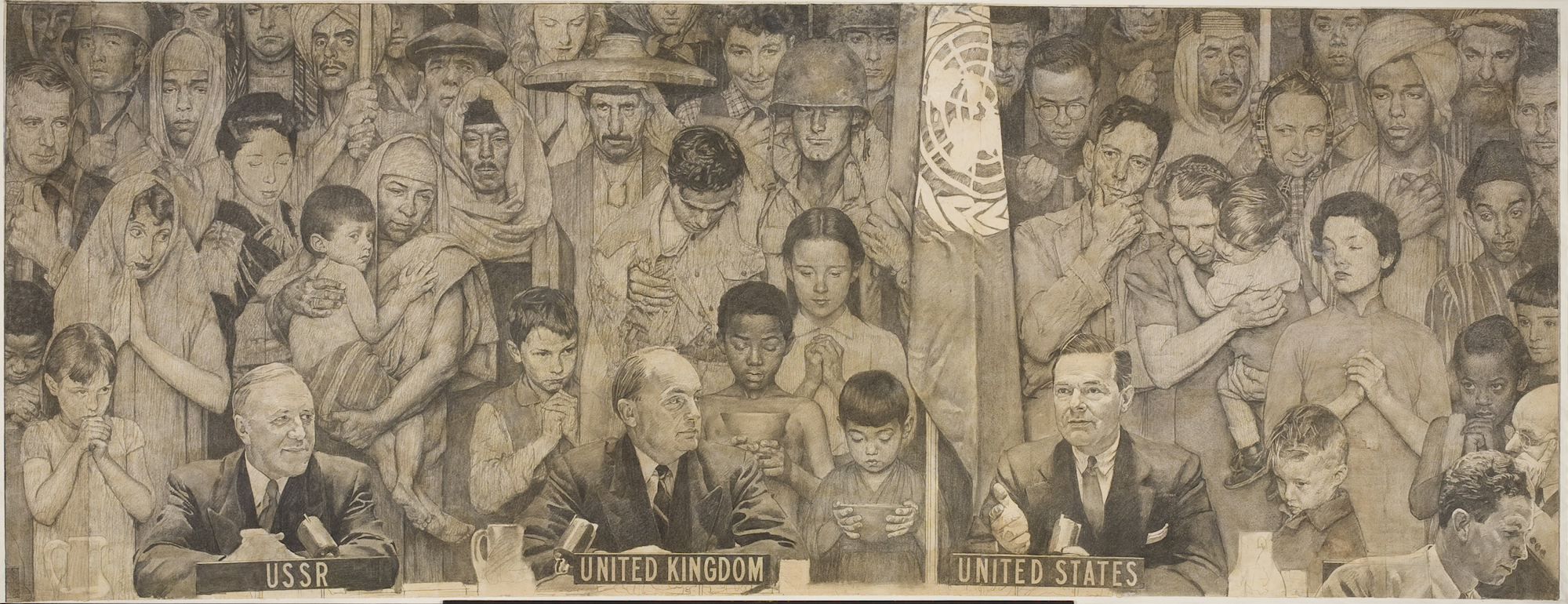

“One day I suddenly got the idea that the Golden Rule, “Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You,” was the subject I was looking for,” Rockwell said. “I began to make all sorts of sketches. Then I remembered that down in the cellar of my studio was the charcoal drawing of my United Nations picture, which I had never finished.” “In it I had tried to depict all the peoples of the world gathered together. That is just what I wanted to express about the Golden Rule.” Rockwell’s Golden Rule painting later served as the inspiration for the stunning glass mosaic that was presented to the United Nations in 1985 as a Fortieth Anniversary gift on behalf of the United States by then First Lady Nancy Reagan, made possible by the Thanks-Giving Square Foundation.

In 2015, the United Nations celebrated their Seventieth Anniversary. A special installation

was created which brought together Rockwell's original drawing, his Golden Rule painting, and other works that reflected his appreciation for humanity as a citizen of the world.

Things to Notice About Norman Rockwell’s Golden Rule

- Mothers of different cultures holding their children

- Mary Rockwell, Norman Rockwell’s wife and the mother of their three sons, holding their first grandchild, Geoffrey Rockwell. Mary had died before Geoffrey was born, but Rockwell brought them together in this work.

- Clothing and objects representing different cultures

Background on Norman Rockwell’s United Nations

In 1952, at the height of the Cold War and two years into the Korean War, Rockwell conceived an image of the United Nations as the world’s hope for the future. His appreciation for the organization and its mission inspired a complex work portraying members of the Security Council and sixty-five people representing the nations of the world—a study for an artwork that he originally intended to complete in painted form. United Nations never actually made it to canvas, but Rockwell’s desire to reach out to a global community found its forum on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in Golden Rule nine years later, in 1961. Pictured here are Security Council Members, Soviet Ambassador Valerian Alexandrovich Zorin, British Ambassador Sir Gladwyn Jebb, and United States Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge.

Of his work on the United Nations drawing, Rockwell said, “Like everyone else, I’m concerned with the world situation, and like everyone else, I’d like to contribute something to help. The only way I can contribute is through my pictures.”

Norman Rockwell

United Nations 1953

Study for an unfinished illustration

Pencil and charcoal on paper

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection

NRACT.1973.113 (M57)

Materials:

Multimedia Resources

GoldenRule

United Nations

- A wide collection of poetry by classic and modern poets which may include:

- Honey, I Love and Other Love Poems by Eloise Greenfield

- The Dream Keeper and Other Poems by Langston Hughes

- All the Small Poems by Valerie Worth

- A Writing Kind of Day: Poems for Young Poets by Ralph Fletcher

- Baseball, Snakes, and Summer Squash: Poems About Growing Up by Donald Graves

- Nameless: A Collection of Poems by Sana Rafiq-Mitchell

- The Best Poems Ever (Scholastic Classics) by Edric S. Mesmer (Editor)

- Leave This Song Behind: Teen Poetry at Its Best by John Meyer et al

- Poetry Speaks Who I Am: Poems of Discovery, Inspiration, Independence, and Everything Else by Elise Paschen and Dominique Raccah

- Songs of Myself: An Anthology of Poems and Art by Georgia Heard

- All the Small Poems and Fourteen More Paperback by Valerie Worth

- Any titles from Poetry for Young People series (Scholastic Books)

- William Shakespeare

- Lewis Carroll

- Robert Frost

- Emily Dickinson

- Rudyard Kipling

- Maya Angelou

- Carl Sandburg

- Walt Whitman

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Access to computers to search online poetry sites such as:

- www.poetry.org

- http://www.familyfriendpoems.com/poems/

- https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/poems-teens

- Class Chart: What We Noticed about Poetry (initiating activity)

- Class charts created during lessons highlighting tools and strategies poets use in their writing.

- Individual and/or class copies of a wide selections of poems to be shared and discussed. The websites above are a great source for poems.

- Paper and writing implements

- Art supplies for original artwork

- Pocket folders, two per student to create a portfolio.

Activities:

- Initiating Activity: Prior to students arrival, place a copy of a poem on each desk (a different poem on each desk). Students should read the poem on their desk. Have students think and jot notes on page about the poem’s structure, theme, mood, language, etc. When students have had chance to read and think about their poems, have them share their noticings. Record their responses on the class chart. Exit task: Ask students what they have noticed about poetry based on the chart that was just created. They may share aloud or you may have them write their response in their reading/writing notebook. Ask some students to share thinking aloud. (Students should keep the poems in notebook for future use.)

- Daily Lessons: Daily lessons should be planned that focus on poetry structures, tools, rhythm and strategies and build on their present knowledge. The poems used in the initiating may be used as models for lessons. Students may use first day poem as well as collected poems for analysis during lessons. Initially, lessons should focus on reading poetry then on writing poetry.

- On-going work: Over the course of this study, students will read poetry, analyzing structure, language, theme, mood, rhythm, etc. As they explore the poems of a variety of poets, they should copy or have copies made of poems that they identify as reflective of themselves. Reading poems may continue after students begin writing original poetry. Poetry shared in lessons, found through exploration or shared amongst each other may all serve as mentors as students write their own poems.

- Essay: During the final week of the study, students should write a one page reflective essay introducing the collection to the reader, explaining the significance of choices contained in anthology. Provide students with models of introductions to use as a mentor text. Magazines include an introduction at the beginning of each issue which is written by the editor. In addition, some of the poetry books, especially those containing collections, begin with an introduction written by the editor.

- “About the Poet” page: A brief (optional) “About the Author” piece may also be included at the end of anthology. Students can find “about the author”mentors on the back of any book. They may choose one to serve as a model as they write their own.

- Original Artwork: Students will be creating an artistic portrait for the cover of their anthology. In addition, they will create an interpretive piece of artwork based to accompany a published or original poem from their collection. Students may use any media which they choose including but not limited to: computer generated art programs, watercolor, and collage.

- Bibliography: A student handout is included which provides students with the structure for citing book and internet sources.

- Celebration: Plan a gallery walk so students can enjoy their classmates anthologies. Due to the length of the collections, you may choose to hold the walk over two days. After the gallery walk, have students come back together to reflect on the process as well as new understandings that they uncovered about themselves and the members of their class community.

Culminating Class Discussion: Referring back to the enduring understandings/essential questions, how has this work changed their thinking about people?

Assessment:

- Did everyone participate?

- Are the requirements for the project met?

- Did students’ reflections demonstrate new understandings?

Standards

This curriculum meets the standards listed below. Look for more details on these standards please visit: ELA and Math Standards, Social Studies Standards, Visual Arts Standards.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.1

- Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.10

-

By the end of grade 11, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 11-CCR text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

By the end of grade 12, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, at the high end of the grades 11-CCR text complexity band independently and proficiently.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.2

- Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.3

- Analyze the impact of the author's choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story or drama (e.g., where a story is set, how the action is ordered, how the characters are introduced and developed).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.4

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone, including words with multiple meanings or language that is particularly fresh, engaging, or beautiful. (Include Shakespeare as well as other authors.)

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.5

- Analyze how an author's choices concerning how to structure specific parts of a text (e.g., the choice of where to begin or end a story, the choice to provide a comedic or tragic resolution) contribute to its overall structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.6

- Analyze a case in which grasping a point of view requires distinguishing what is directly stated in a text from what is really meant (e.g., satire, sarcasm, irony, or understatement).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.7

- Analyze multiple interpretations of a story, drama, or poem (e.g., recorded or live production of a play or recorded novel or poetry), evaluating how each version interprets the source text. (Include at least one play by Shakespeare and one play by an American dramatist.)

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.1

- Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.10

-

By the end of grade 9, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, in the grades 9-10 text complexity band proficiently, with scaffolding as needed at the high end of the range.

By the end of grade 10, read and comprehend literature, including stories, dramas, and poems, at the high end of the grades 9-10 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.2

- Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.3

- Analyze how complex characters (e.g., those with multiple or conflicting motivations) develop over the course of a text, interact with other characters, and advance the plot or develop the theme.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.4

- Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in the text, including figurative and connotative meanings; analyze the cumulative impact of specific word choices on meaning and tone (e.g., how the language evokes a sense of time and place; how it sets a formal or informal tone).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.5

- Analyze how an author's choices concerning how to structure a text, order events within it (e.g., parallel plots), and manipulate time (e.g., pacing, flashbacks) create such effects as mystery, tension, or surprise.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.6

- Analyze a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.7

- Analyze the representation of a subject or a key scene in two different artistic mediums, including what is emphasized or absent in each treatment (e.g., Auden's "Muse des Beaux Arts" and Breughel's Landscape with the Fall of Icarus).

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9

- Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.10

- Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.5

- Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1-3 up to and including grades 11-12 [link to="CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.11-12"]here[/link].)

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.6

- Use technology, including the Internet, to produce, publish, and update individual or shared writing products in response to ongoing feedback, including new arguments or information.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.9-10.1

- Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.9-10.10

- Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.9-10.5

- Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific purpose and audience. (Editing for conventions should demonstrate command of Language standards 1-3 up to and including grades 9-10 [link to="CCSS.ELA-Literacy.L.9-10"]here[/link].)

- CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.9-10.6

- Use technology, including the Internet, to produce, publish, and update individual or shared writing products, taking advantage of technology's capacity to link to other information and to display information flexibly and dynamically.

- D2.Civ.10.9-12.

- Analyze the impact and the appropriate roles of personal interests and perspectives on the application of civic virtues, democratic principles, constitutional rights, and human rights.

- D2.Civ.7.9-12

- Apply civic virtues and democratic principles when working with others.

- D2.Soc.1.9-12.

- Explain the sociological perspective and how it differs from other social sciences.

- D2.Soc.2.9-12.

- Define social context in terms of the external forces that shape human behavior.

- D2.Soc.3.9-12.

- Identify how social context influences individuals.